Safe retries and idempotency

In the case of network issues or other unexpected behavior, ICP clients (such as agents) that issue ingress update calls may be unable to determine whether their ingress request has been processed. For example, this can happen if the client loses its connection until the request status has been removed from the state tree, since ICP will remove the request from the system state tree some time after the ingress expiry.

This can be risky as the application might decide to retry transactions, potentially leading to serious security vulnerabilities such as double spending.

Thus, it is important to design and/or use canister APIs such that it is possible to retry requests safely, even when the ICP provides no information about previous request attempts. This page describes general approaches that both the canister authors and the clients can adopt to enable safe retries.

Please read the reference on ingress messaging to learn about the messaging basics and potential errors.

Idempotent canister APIs

We say that a canister endpoint is idempotent if executing it multiple times is equivalent to executing it once.1 Whenever an endpoint is idempotent or can be made idempotent by the developer, this provides an easy way to implement safe retries.

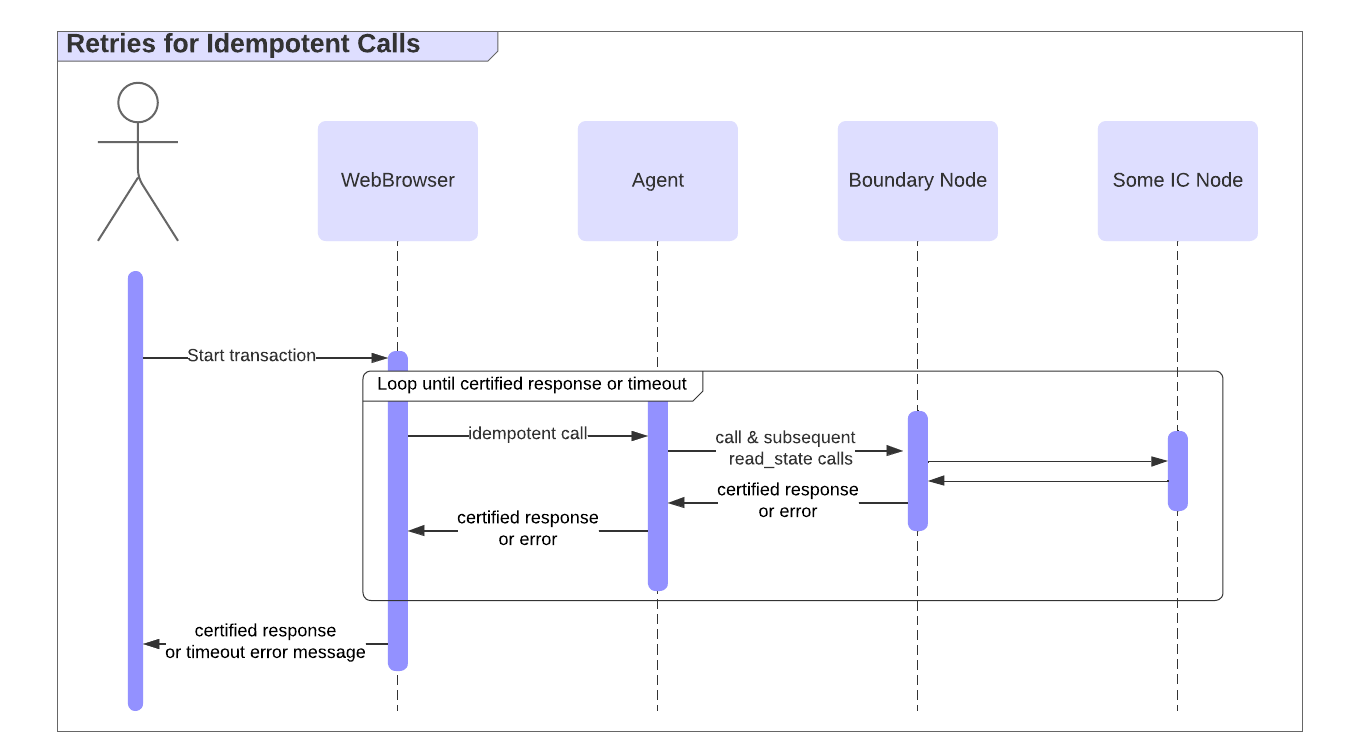

Given an idempotent endpoint, you can implement retries by retrying the call until you observe a certified response, either a replied or rejected status; see the illustration below. If such a response is ever observed, it's sure that the transaction has been executed at least once which, thanks to idempotency, has the same result as executing it exactly once. However, the application may not be willing to wait for a response indefinitely and a timeout could be implemented. Upon timeout, an error should be displayed to the user instructing them to wait until the latest message that has been sent has expired (as defined by the request's ingress_expiry) and then manually check the status of the transaction. Ideally, timeouts should be rare and not occur during normal operation.

Below are two approaches to making endpoints idempotent: sequence numbers and (time window) ID deduplication.

Update sequence numbers

An endpoint can make use of sequence numbers to provide idempotency by taking a sequence number parameter in addition to other parameters. In the extreme case, a canister could keep a single expected sequence number for every endpoint, and a call could only be accepted if it contained the next expected sequence number, causing the expected sequence number to be incremented upon call execution. This trivially implies that any call can only be executed once. More practically, an expected sequence number is kept for each caller principal, or, in case of ledger-like canisters, each ledger account. Note that Ethereum implements this mechanism.

The advantages of this approach are:

- Sequence numbers are simple to implement and understand.

- When applicable, it has a modest memory footprint because only the next expected sequence number must be stored (for example, per active account).

The approach also has some disadvantages:

- It limits the throughput. When per-caller sequence numbers are used, it means that the caller can generally perform only one ingress call per consensus block, translating to a throughput of about 1 call per second for that user.

- It limits concurrency. The user has to sequentialize all their calls. This can be difficult when the user is using multiple clients or devices to access the canister, for example. This concurrency problem also makes the approach inapplicable to cases where anonymous users are allowed to trigger update calls.

- If the sequence number is stored per user or per account, tracking them for too many users can exhaust the canister memory, even if each individual number is small. This could, e.g., be exploited by an attacker to exhaust the memory. The approach is thus best suited for cases where the user has to pay for the usage in some way (e.g., the ledgers usually require a fee to both create an account and transfer funds), which thwarts attackers by requiring them to invest significant funds in an attack.

ID deduplication

Another approach to idempotency is to make the calls uniquely identifiable on the canister side (e.g., by using user-chosen IDs, sequence numbers, or a combination of several argument fields) to make sure a given call is executed at most once. The canister then deduplicates calls before executing them; if a call with the same ID has been executed previously, the new call is simply ignored (potentially returning the result of the previous call). Thus, the user can safely keep retrying the call until they get a response.

For example, the ICRC ledger standard provides deduplication in this way. Using identical values for all call parameters, including the created_at_time and memo parameters, when issuing a transaction makes the transaction call idempotent by deduplicating calls with the same parameters.

However, a naive implementation of this approach can exhaust the canister memory, as all successfully executed IDs need to be kept around forever.

Thus, the deduplication is usually time limited to a certain time window. For example, the ICP ledger uses a 24 hour window, and the ICRC standard defines a configuration parameter TX_WINDOW that determines the window length.

Moreover, the ICP/ICRC ledgers use the created_at_time parameter to limit the validity period of a call. Roughly, the call is only considered valid if its created_at_time is not in the future and at most 24 hours in the past.2 This avoids the problem where the deduplication window expiring would allow a retried call to succeed again.

But even with this improvement used in the ledgers, the time window approach implicitly assumes that the client will be able to get a definite answer to their call within the time window. For example, after the 24 hours expire, the user cannot easily tell if their ledger transfer happened; their only option is to analyze the ledger blocks, which is somewhat tedious, and has to be done carefully to avoid asynchrony issues; see the section on queryable call results.

Relying solely on a time window for deduplication does not guarantee bounded memory usage. In theory, an unlimited number of updates could occur within the time window, though in practice, this is constrained by the scaling limits of the ICP. The ICP/ICRC ledgers thus also define a maximum capacity: a limit on the number of deduplicated transactions (i.e., deduplication IDs) that can be stored in their deduplication store. Once this capacity is reached, further transactions are rejected until older transactions expire from the deduplication store at the end of the time window. Yet another extension of the approach is to guaranteed deduplication for the stated time window as above, but keep storing deduplication IDs even beyond that window, as long as the capacity is not reached. This way, the clients obtain a hard deduplication guarantee for the time window, and a best-effort attempt to deduplicate transactions even past the window.

An alternative is to do away with the time window, and store the deduplication data forever. This requires multiple canisters to prevent exhausting the canister memory, similar to how the ICP/ICRC ledgers store the transaction data in the archive canister. This shifts the tedious part of querying the deduplication data (e.g., ledger blocks) from the user to the canister.

Summarizing, the advantages of this approach are:

- It can support high throughput.

- It requires no synchronization on part of the user, and supports use cases like multiple devices.

The disadvantages are:

- It is more complicated to implement than sequence numbers.

- If a time window is used, it usually implicitly assumes that the user learns the call outcome within the time window.

- The memory usage can grow fairly high with high supported throughput and long deduplication windows. For example, supporting 100 transactions per second with a deduplication window of 24 hours can require hundreds of megabytes of heap space. This can be mitigated by using multiple canisters to store the deduplication data, at the expense of further implementation complexity and higher latency.

Other approaches to safe retries

In absence of idempotent endpoints, or even in addition to them, clients may be able to use other endpoints to make their retries safe.

Queryable call results

If the canister, in addition to the update endpoint, also exposes a query that can inform the user of the result of the update, the client can also use this for safe retries as follows:

- Attempt to perform the update.

- If the result of the update is unknown (e.g., not present in the ingress history anymore), query the call result endpoint to determine whether the update was applied or not. Moreover, one needs to ensure that the previously sent call cannot be applied in the future. If both of these are true, the call might be retried or safely reported as failed.

In practice, this pattern may be more complicated. For example, the ICP ledger exposes a query_blocks method that can be used to implement the above pattern for transfers initiated as ingress messages:

- Call the

query_blocksmethod on the ledger to determine what the last block (as specified in thechain_lengthfield of the response) currently is. Let's call thislast_block. - Attempt to perform a transfer. This ingress message includes an

ingress_expiryfield. - If the result of the transfer is unknown, call the

read_stateendpoint on the ledger canister to obtain the/timebranch of the system state tree. Repeat this until the reported time exceeds theingress_expirytime. This ensures that the transfer will not be applied at a later point. - Call the

query_blocksmethod on the ledger again to retrieve all ledger blocks sincelast_block, and check that thetimestampalso exceeds theingress_expirytime. Then, scan through the returned blocks to determine whether the transaction has been included or not.

2-step transfers

Another approach applicable to ledgers (such as ICRC-1 or ICP) is to perform transfers in two steps:

- First, transfer the tokens to an intermediate subaccount of the sender that's specific to this transaction. For example, if the transaction has a unique ID, the client can hash the ID to obtain a subaccount. The transferred amount should be the desired amount plus the ledger transaction fee.

- If the result of the above transfer is unknown, query the balance of the transaction-specific subaccount. Like in the "queryable call result" approach, this should be repeated until the

timestampaccompanying the response exceeds theingress_expiry. If the balance is 0, the transaction can safely be reported as failed, or it can be retried (starting from step 1). If the balance is at least the expected balance, one can proceed. - If the transfer to the transaction-specific subaccount succeeded (as determined either by the transfer result or by the balance query above), the client sends another transfer from the transaction-specific subaccount to the desired target account. This can be repeated as many times as necessary until a result of the call is known. Once a result is known, the overall transfer can be declared as succeeded, even if this step fails with an error, as this signifies that some previous attempt to transfer the money to the target succeeded.

- "Equivalent" is meant from the user perspective here. Multiple executions may trigger changes such as those in the canister's cycle balance, but they are not relevant for the user.↩

- More precisely, the ledger also allows for a small time drift of

created_at_timeinto the future, which has to be taken into account when clearing the deduplication window.↩